Work the problem: Hybrid Teaching

"Work the problem"

I really do love that line from Apollo 13. In the film, Ed Harris plays Flight Director Gene Kranz whose calm composure and levelheadedness helped keep three astronauts alive. Unfortunately, this line may be a bit of poetic license and slightly hyperbolic (see what I did there?!). Regardless, it makes for one of the most succinct statements on solving problems: focus on the problem itself.

Whenever we get bogged down in some type of problem, the reality is we have trouble seeing how to solve it because we're often so consumed by the panic that surrounds it. If we can take a step back, follow a few steps, and give ourselves some room to think more clearly, the solution generally presents itself.

Fortunately, there's a well-defined problem-solving pattern that I teach to computer science students. While it may seem incredibly elementary, we're going to apply the same process to a novel, difficult problem: hybrid teaching.

Step 1: Identify the problem

My reading volume has upticked considerably during quarantine. I even re-upped my Audible subscription. Every morning since the start of September, while I walk the dog, I've been "reading" Yuval Noah Harari's Homo Deus. In it, he describes the dichotomy between subjective and objective thought; however, he also attempts to illustrate a bridge between the two: the "intersubjective" realm. The term refers to the shared agreement of meaning between multiple people. I reference this because one of the most challenging parts of solving any problem is to squash the competing notions of what the problem actually is and come to a consensus that can then guide the rest of the process. Arguably, this step is the most important in the process. Get it wrong and everything you'll eventually build will be centered around solving a problem that doesn't actually exist.

What is the problem with hybrid teaching?

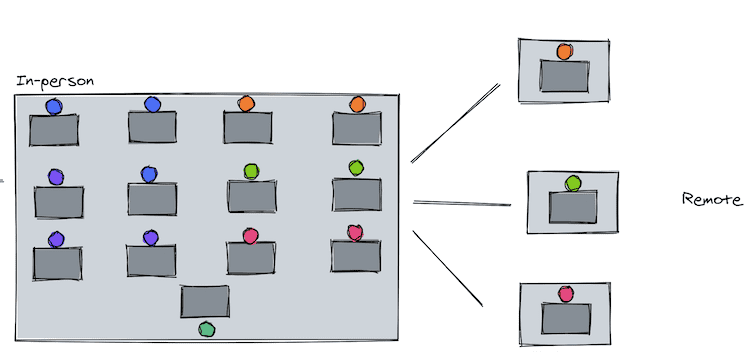

Hybrid teaching is a model wherein an educator is responsible for developing lessons that are simultaneously presented to multiple sets of learners. In this context, the two sets we'll refer to are in-person and remote. While there may be some discrete subdivisions we can make from this larger issue, the problem lies in the fact that a teacher is now responsible for engaging two sets of learners that are in completely different places. The problem can be framed in this question: How can an educator deliver the same quality of instruction to two separate sets of learners as she can with one set of in-person learners?

I've chosen this question to frame the problem because this is the feedback I continually hear from different groups (teachers, parents, students): how can this be like "real" school? That leads me to ask, what's changed that makes our current situation not real school?

Well, we have some students in-person and some students off-campus. Is anything else really different? In a moment, we'll enumerate the various constraints on the learning environment, but I would argue that the only fundamental difference in a typical school setting compared to this hybrid purgatory we're all in is this division of learners into two, seemingly, discrete sets.

With our problem clearly defined and focused on the gap in quality between teaching either one or two sets of learners, we can move onto identifying and defining our constraints.

Step 2: Identify the constraints

Constraints are the different challenges that need to be addressed in order for a problem to be solved. Ideally, all constraints would be addressed, but not all solutions are perfect. Often, one of the most pressing constraints is that of time. In the words of Silicon Valley's elite: ship it; sometimes we have to get the minimum viable product (MVP) out to consumers as quickly as possible. However, with ample time and the ability to iterate, we can generally create better conditions to address all constraints related to a problem.

What are the constraints for hybrid teaching?

I posit that while some of these constraints are related specifically to a hybrid model, most are simply being amplified by the pandemic itself. In the context of 2020 (hopefully, only 2020 🤞) these two paradigms are inseparable.

-

student-to-student interaction is hindered: most definitions of "good" teaching in 2020 would include some components of group work or, more simply, collaboration between students. Arguably, conditions due to the pandemic - like social distancing in classrooms - have restricted instructional choices.

-

active-learning is unsettling: again, framing good teaching within the context of modern pedagogical trends, active-learning strategies should be present in a lesson. Active learning can simply be described as any activity that helps learners build knowledge, develop skills, or practice concepts so long as they are producing some kind of product. More simply put: active learning is not passive learning (long lectures...😴). However, in the unfamiliar terrain of the hybrid model, it's difficult for teachers to give up this level of control and "face-time" with students during sync sessions.

-

infrastructure is needed: in order to deliver a hybrid lesson, there's a significant amount of technological infrastructure that must be present. Some of this is very visible (devices, webcams, meeting software) but much of it is not ever seen (network bandwidth, protocols, etc...).

For the purposes of this post, I'd like to focus on the constraints most in the control of teachers: the inherently pedagogical elements of student-to-student interaction and the selection of active-learning strategies. While it would be great - especially for you all reading this! - to go ahead and jump to how to solve these two pieces, there's another important step we need to complete first: we must define success.

Step 3: Define what success looks like

If you're looking for a mental model to this process, think of this: earlier, we defined our problem. Essentially, that's our starting place. What we're about to identify is where we "end" this journey. The constraints we outlined previously are "waypoints" that need to be visited along the way from start to finish.

To define the "ending," I suggest we turn back to one of the questions we encountered earlier: how can we make the hybrid environment look more like "real" school? To answer this question, we'll have to address our two main pedagogical constraints.

Step 4: Plan

Let's start our planning by attempting to address our two pedagogical constraints: student-to-student interaction and active-learning.

Perception

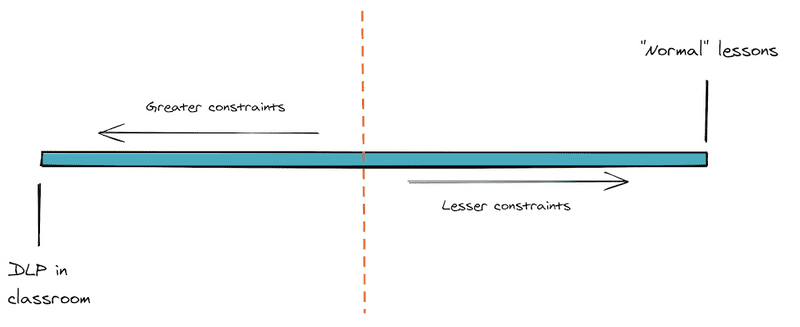

The perception that most people have when thinking of the difficulties associated with hybrid learning is in line with this spectrum: on one end, we have "normal" lessons that would be delivered if there were no constraints placed on us by the pandemic. There would be no social distancing, all learners would be in one classroom, and the teacher would be free to teach as they did before. On the other end we have a distance learning plan (DLP) that can take a variety of forms but, universally, is comprised of two sets of learners.

Reality

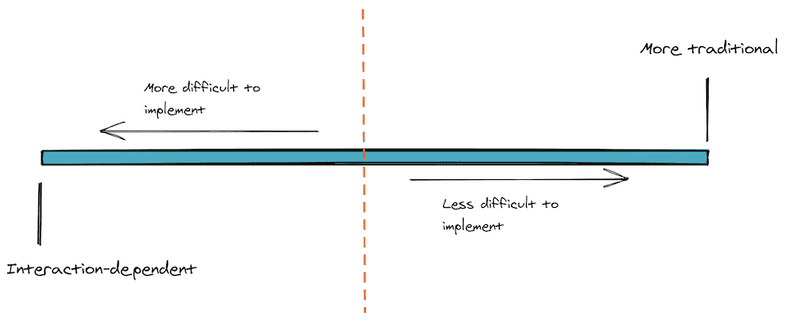

The reality though is quite different. While it would appear that there's a greater set of constraints on one setting versus the other, this is not the case. The model below is more accurate at describing our hybrid model during the pandemic.

Classes typically filled with active-learning techniques, rich with student-student interaction face the biggest difficulty in adapting to the hybrid model. On the other end of the spectrum, passive-learning classes that are mainly comprised of lecture or direct instruction are significantly easier to implement in this setting: point a camera at a teacher, let them talk for n minutes, assign the reading for the next day's class, and call it a day. Do the students even really have to be there for it?

How can we encourage student-to-student interaction?

This could be the greatest constraint on the hybrid model. Teachers around the world have difficulty encouraging students to engage with each other about the material. We've all been in rooms where conversations quickly get off-track, the quality of work drops significantly, or a student asks, "Can't I just work by myself?"

The reality is teachers need a strong foundation in understanding the dynamics of this classroom setting before being dropped into a hybrid model. However, that caveat is a luxury that we can't afford during our current state. Given our conditions, here are some considerations that encourage students to interact with one another during a hybrid lesson.

-

Use breakout rooms: these are the digital version of pods/tables many of us have become accustomed to using in the classroom. Depending on your tech stack, there are different ways of achieving these smaller meetings. Some platforms, such as Zoom, have had this feature for quite some time. Others, like MSFT Teams, are in the process of developing this built-in tool. If - like the school where I work - you're using Teams and want to start with breakout rooms straight away, try this:

- Create private channels for each group

- Add students to their group's channel

- From the whole-class meeting, direct them to their channels for group-work

- As the teacher, you have access to all the channels and can easily drop in to check on things and provide support

-

Chunk lessons: The amount of sync time we have with students varies. When considering how long remote learners may be spending on a device, it's important to vary instructional strategies. This is easier said than done in a distance setting; while we can mix-up what we do during class, students are still sitting in front of a screen. This makes breaking lessons into more manageable, smaller segments a critical step in determining success. A great pattern is one stolen from the world of soccer training: a whole-part-whole lesson. In a forty-five minute hybrid class, spend the first fifteen minutes on one activity that involves a whole-class meeting. For the middle portion, design an activity that allows students to break off into groups and work together. Finally, bring them back into the whole-class meeting for them to share their work and use this as your opportunity to clarify any misconceptions.

Design an inclusive setting

This last point deserves its own subheading. One of the greatest threats in this hybrid setting is the exclusion of one set of learners. When I was first forced to think about this type of teaching, my concern was centered on the remote students; I assumed the the majority would always be in the classroom. However, especially with the prevalence of A/B cohort scenarios we've seen around the country, that's not always the case. At times, the students in the classroom are the ones in the minority.

Knowing that, it becomes critical for teachers to plan ahead and develop groups/breakout rooms around who is in-person and who is remote. These groups should be blended to encourage a connection between the two sets of learners.

How can we facilitate active-learning?

There's a significant amount of research into what constitutes authentic active learning. One common component is what was mentioned above: allowing students to collaborate. In modern pedagogy, the connection between active and authentic learning is becoming more and more clear. In readying students for the real world, our classes should mirror the environments and circumstances students can expect to encounter. A critical component of any real-world scenario is having to collaborate with others. Further, in the real world, students will have to solve problems and create solutions that may deviate wildly from any preplanned, teacher-generated "solution."

All this to say: we have to get comfortable giving up a bit of control. This is especially daunting in a hybrid setting. Imagine turing students loose to work in breakout rooms for a significant portion of the sync time you have with them for that day. What if it doesn't go well? What if it's wasted? What if they don't reach the solution you'd hoped for? These thoughts run through everyone's heads. However, with time and practice, it becomes easier to facilitate these types of activities and - in the long run - the pedagogical gains far outweigh any short-term anxieties.

Step 5: Iterate

Your first solution won't be your last. Lesson after lesson or week after week, you'll need to filter out the activities that didn't work and replace them with something else. It will be easy to tell what fits and what doesn't, but it will take some time to adapt pre-COVID strategies to this new hybrid model.

Keep one thing in mind, though: don't reinvent the wheel each iteration. Little changes add up over time; you don't have to solve everything in the second round. Incremental change based on careful revision is the key to success.